Carl Schmitt - The Man

1889-1989

“Man is only happy in cooperating with his individual destiny.”

Looking at a painting by Carl Schmitt in an exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum during the early 1920s, a viewer reportedly proclaimed, “This couldn’t have been painted by a human hand!” Carl Schmitt’s lifelong study of color and form, which arose from an untiring pursuit of beauty in modern art and humanity, enabled him to achieve what another critic, the Irish poet and friend Padraic Colum, described as “giving us rapture” (The Commonweal, 1930). His talent allowed him to exhibit at such world-renowned places as The Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, The Chicago Art Institute, The Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Brooklyn Museum. He was one of the founding members of the Silvermine Guild of Artists in 1922, and in 1928 was a guest at Yaddo, the famed New York artists’ and writers’ retreat.

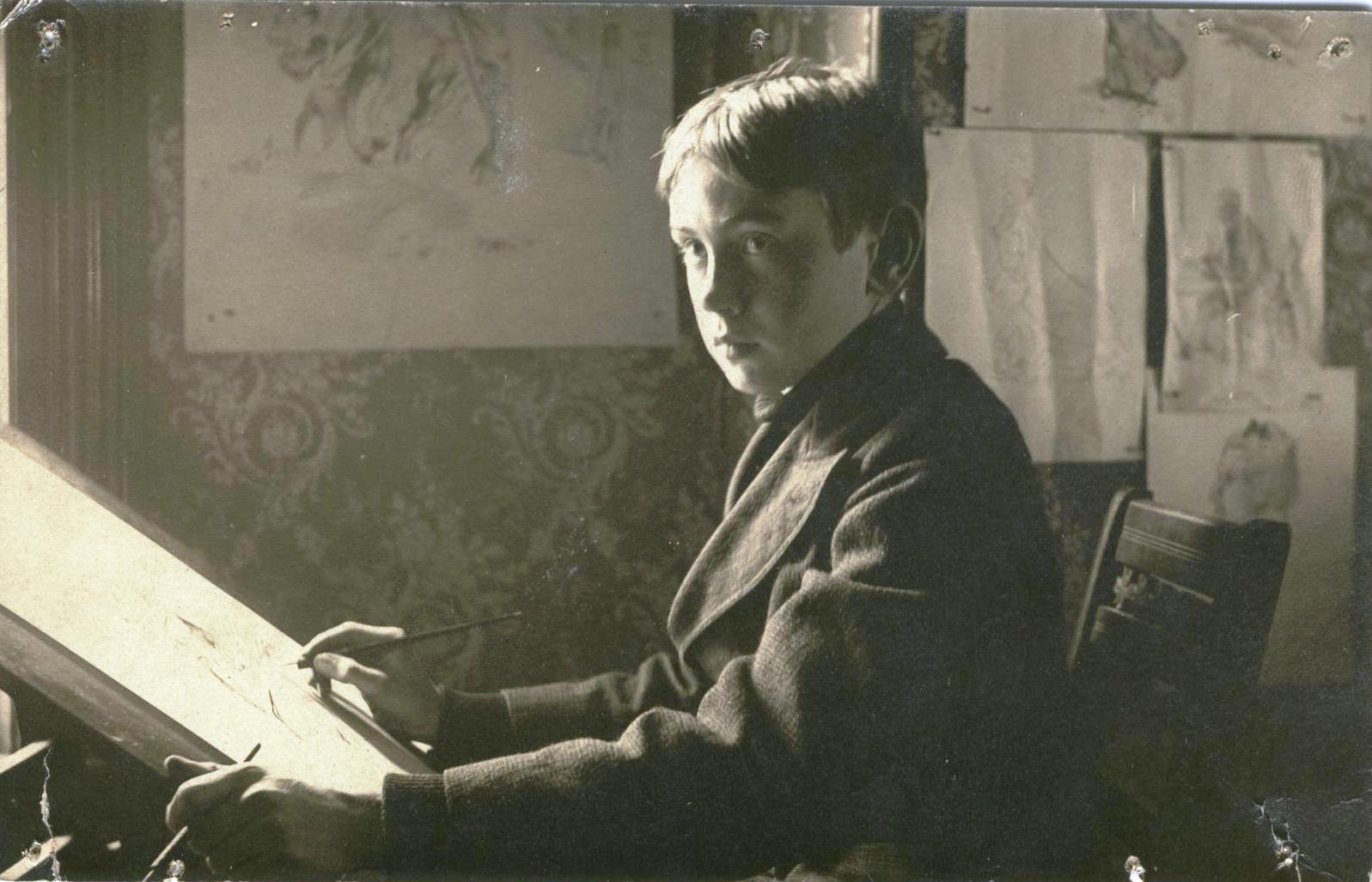

The Early Years

a young Carl already showing artistic promise

Schmitt's fierce pursuit of the arts began early. Born in 1889 in Warren, Ohio, to Prof. Jacob Schmitt, an accomplished musician and music teacher, and Grace (Wood) Schmitt, the young Carl received ready encouragement to further his artistic interests and evident gifts. These found wider scope through his friendship with a Youngstown photographer, Jimmy Porter, and with Zell Hart Deming, the owner of the Warren Chronicle. As a patroness of the arts, Mrs. Deming held an informal salon for local writers and artists. Quickly recognizing the talent of this spirited teenager, she encouraged his ambitions, and with her financial help, Schmitt left Warren at age seventeen to begin formal studies in New York.

Between the years 1906 and 1912 in New York, Schmitt first attended the Chase School, where William Merritt Chase was still giving classes and Robert Henri was the dominant figure. The following year, he switched to the National Academy of Design to study under Emil Carlsen. Schmitt excelled at the Academy, studying intensely the fundamentals of color, line and form, and gaining an intimate understanding of their individual properties and relations. He won a best picture award each of the years that he was there. He had great respect for his teachers, but especially Carlsen, keeping for the rest of his life several pages of quotes from his class. Nonetheless, Schmitt was determined to be his own man in art. Carlsen had offered to teach him privately, but Schmitt was a man of strong convictions, who was soon heading in a different direction. He wanted to understand the “energy that is behind the arts” and which “no one can in terms of science explain.”

Exploring the Mysteries of Painting

“ I want to paint a canvas…that will be nothing but harmonious tone.”

After leaving the Academy, Schmitt began painting in New York and then in Ohio, where he received a number of commissions. Determined to round out his training, he spent a year in Florence, Italy, at the sponsorship of Mrs. Deming. There, in 1913-1914, he studied under Mathias Duval at the Academy of Fine Arts. He soon discovered Michelangelo, Raphael, and the Italian countryside and spirit, from which he began to derive his own personal aesthetics—an aesthetics that drove him throughout his life.

An early self portrait completed by the artist during his time in New York.

By 1916, Schmitt had set up a studio in New York. He had written, “I want to paint a canvas…that will be nothing but harmonious tone.” Joining him there was a friend from Ohio, Zell Hart Deming’s nephew, Hart Crane. The celebrated American poet was still an aspiring writer at the time, and Deming charged Carl with looking after him. Schmitt saw Crane’s genius, but noticed a lack in his mastery of the rhythms of words. He worked with the poet at length, composing and reciting together each evening to develop the craft. Crane wrote to his father: “Nearly every evening since my advent has been spent in the companionship of Carl. Last night…we talked until twelve, or after, behind our pipes. He has some splendid ideas.”

Crane was not the only one to experience the artist’s keen mind and gracious openness of spirit—and discerning eye for talent. Carl Schmitt was a gifted conversationalist and thinker, but always showed an easy and generous affability with all he met. These qualities gained him many friendships, including those with the poet Conrad Aiken, writers Earl Derr Biggers (of Charlie Chan fame), Van Wyck Brooks, Padraic and Molly Colum, and the documentary movie pioneer Robert Flaherty. These and other friendships gave Schmitt a constant occasion to expound and clarify his theories of the arts, often with wit and humor. These profound insights and aesthetic theories, summarized in his many essays scattered throughout his notebooks, powered both his life and work.

A New Home and Family

Carl and Gertrude in Silvermine, Connecticut, c. 1920

Within a few years, however, Schmitt developed a desire for a quieter life where he could paint and think in peace. At the urging of another Ohio artist friend, Addison T. Millar, he headed to Silvermine, Connecticut, where he bought an acre of land with a ruined eighteenth-century stone structure across the road from the American sculptor Solon Borglum. During the building’s restoration, he and his new bride, Gertrude, lived in a wooden shack that Schmitt had made. This “first home” was quite a change for the new bride, the daughter of the Beaux Arts architect A. W. Lord, who was used to servants and the cultural life of New York City. In this quiet and beautiful setting, Schmitt was able to continue his study of the arts.

The Schmitt family on the porch, 1936

Though he now lived far from the bustling crowds, Schmitt still was able to impress critics and public alike. In the late twenties, he took the entire family for an extended stay in Chartres, where he studied its glorious cathedral and worked in its shadow. Dedicating his entire life to the pursuit of beauty “no matter the consequences,” Schmitt and his devoted wife Gertrude endured many hardships, including the severe poverty of the Depression, the burdens and joys of a large family, and chronic illness.

Italy

A severe bout of tuberculosis, a disease that he had been fighting since boyhood, came on in the mid-1930s. At the urging of his doctor and through the generosity of friends, he entered a sanatorium in the Italian Alps. It was a trying time for him and the family, forcing even the sale of his studio. Gertrude and the ten children followed six months later. For Schmitt, Italy was the center of all Western Civilization and culture. A true devotee of Western art and a great lover of Michelangelo, he decided, as he recovered, to stay and live the life of an expatriate painter with his family in Rome.

The influence of Schmitt's time abroad can be seen through out the rest of the artist's career

In Rome, he met the philosopher George Santayana, whose ideas on art Schmitt believed to be very good, but too materialistic. He also first met in person the English Catholic apologist and historian Hilaire Belloc, with whom he had carried on an extensive correspondence for over twenty-five years. Schmitt appreciated many of Belloc’s qualities, and the two had developed a good friendship.

In a letter dated July 8, 1913, Belloc thanks Schmitt for sending him an etching, which is “a most beautiful piece of work.” Some of these letters evidence Belloc’s desire to show Schmitt some of his “dry points” though “I’m no good at it but it amuses me and I like to do things with my hands.” At a later time, Schmitt regularly wrote a column for Chesterton’s Weekly Review, when Belloc was its editor. But Carl Schmitt’s dream of permanently residing in Italy was short lived, for Hitler and Mussolini had their own plans.

The Consummate Friend and Artist

Upon returning to Silvermine in 1939, the family resumed residence in their old home on Borglum Road. This house soon proved inadequate for their needs, and so through the generosity of Gertrude’s father—who owned quite a few acres on Borglum Road—they built a new home on some donated land. There they remained for the rest of their lives, Schmitt now painting in a studio that his sons had built in 1950 behind the house. (This structure now serves as the office and gallery of the Foundation.)

In this new home and studio, he continued painting, wrestling more than ever with the “mysterious workings” at play in the arts. Always positive, since, as he would say, he is simply being a realist, Schmitt did not take the attitude that modern art was necessarily bad. It was simply immature and too subjective and emotional, thereby not living up to its natural possibilities.

Friends characterized Carl Schmitt as a man truly respectful of the individual person. Despite the poverty and troubles that sometimes seemed to overwhelm him, he treated people amiably and with humor. The intensely strong beliefs, great wit and profound ideas of Schmitt never closed him off from his contemporaries whose ideas (like the communism of his friend Charles Reiffel) many times differed greatly from his own. He was genuinely a man in pursuit of the truth of art and life.

Thus, he continued to paint and write in relative isolation from 1940 to 1988, stopping only a few months before his death at the age of 100. His death on October 25, 1989, his seventy-fifth wedding anniversary, was an ironic twist that would have received a good deal of attention in Carl Schmitt’s book of humor.

“Man is only happy in cooperating with his individual destiny.

All men are destined to perfect virtue.

Some men are destined to achieve virtue before death

Some are destined to achieve it after death.

It is a special mark of providence to have the opportunity of complete humility before death.

The longer before death it is – the greater the mark of God’s love.”

Self Portrait of the artist, Oil on Panel