Wind in Art, 1925

Woman in Irish Coat, Oil on Canvas, Date unknown

Great art, major art, is dependent upon wind. Granted authentic lyricism in two men in any art, the major poet differs from the minor in wind only. Call it endurance, perseverance, sustainment or what you will; I prefer wind.

In other words the three realities of the imagination: lyric poetry, epic poetry, and dramatic poetry (or what are called three in this age of separation and analysis) are one. They differ in degree of intensity and not in kind.

“the three realities of the imagination: lyric poetry, epic poetry, and dramatic poetry (or what are called three in this age of separation and analysis) are one. ”

The lyric poet in any art, the minor poet, has wind enough to capture the “illusion,” the wonder of beauty. He is essentially musical, moody, and at best with vision. This “illusion” is part of esthetic truth, and I say, that whoever scandalizes illusion and mocks it shall not enter into the kingdom of beauty. I repeat that “illusion” is part of the poetic truth, it is the first part, and without it there is no beauty at all. But your true minor poet stops here. He is one who sits down and is content to live forever in the memory of the City seen in all the wonder of mirage. This beautiful superficiality of color and light, form in light, this accident, this trick of nature, symbol of a miracle, is enough for him. “Touch it and you spoil it” is the slogan for him and his kind. He sees with the heart, his vision is emotional and of one plane, a constantly curving surface. Do not be superior and do not underrate him, however. He is the symbol of the innocence of childhood. And being a child he lacks wind.

Now the epic is the lyric sustained until the mirage (that first memory of reality) has faded and is gradually replaced by a clear vision of the City, itself standing steady in the distance, an appearance replacing mirage. Here is the second stage of your man of wind—a state of rest and preparation; in essence stable and objective, the conservative poetry, processional, the second reward of the persevering lyricist. He is your neo-Greek. He is closer to “reality” but does not touch it yet. He rests largely in the enjoyment of the vista. He has added space and shadow to the form of the light of the mirage. He is happy with another plane—the horizontal and the vertical stand clear. A natural thing.

A young Carl Schmitt in the studio

But your man of wind goes on. He risks all to gain tangible reality. The essence of each stage is form. The lyric essence is form suggested, form as light. The epic essence is form in appearance—form andspace, light and shade. The third stage is the lyricism sustained into form tangible, poignant, climactic. And this is the mark of your major artist: without losing memory, the mirage, the illusion, he grasps the tangible in three planes and senses fully those intellectual things: character and the dance—rhythm. He is capable of many categories. He juggles three or more melodies. He works the piccolo and the tympani. All is in perspective. His line is acrid-sweet and bitterness is made beautiful. If he sculpts, his large oppositional thrusts of plane are a unit of Gothic harmony. He has added the intellectual imagination to the emotional and has descended into the City.

Your major poet in (any art) has struck his fist against reality. He sees red and he sees black, desperation and the void, not for themselves but as foils, as counterweights only to make his first lyricism more poignant in comparison. He has largely heightened the light of emotional beauty with the darkness of intellect. He has set off the form of lyricism with the form of the dramatic, which is void. The point is that each exists for the sake of the other.

“But your man of wind goes on. He risks all to gain tangible reality. The essence of each stage is form. ”

Again let me emphasize, an epic, in any medium of space or time, is an outgrowth of a lyric, a superstructure, reward to the lyricist of great desire and wind. A dramatic (in any art) is an outgrowth of a lyric, a reward to the lyricist with blood to shed (and wind). We shall say nothing of the second epic—the rest after the fight, the beatific vision of art.

Those who have seen it do not deny our thesis. They tell us, however, that we have it all backwards. They say indulgently that we have seen something of the truth and imply that we have seen it hind side foremost. They say that the dramatic is an outgrowth of the epic and that the lyric is an outgrowth of the epic and the dramatic. They are esthetically athletic, and speak of endurance, or they are saintly and mystical and have goodness for a goal, rather than beauty, and talk of the grace of perseverance; but they are few and unknown today in our progressive America. Meanwhile, there are many of us; and we see things backwards, and are pedestrian. And we call it wind.

Madonna in Black Kerchief, Oil on Canvas, Date unknown

Theory Applied to Painting

Let us skillfully apply this theory of wind to the art of Painting. Now painting, pure painting is a lyrical art (like letters and music). In its purity it is concerned with the mirage of form in light, the first fresh vision of youth, spontaneous with the mood of wonder and essentially melodic. It sees all with the emotional imagination and consequently beauty is a one-plane affair. For when form is imagined exclusively in one plane, design is purely melodic and the greatest opportunity is given to color. The lyrical imagination, in seeing form in one plane, unconsciously sacrifices much of form (by eliminating void) and values (by eliminating shadow) in favor of color, light, quality, and line.

The lyric art of painting, this pure painting (and as such it is a minor art) is to be found in its perfection in children up until the age of 14 or thereabouts. We have failed to grasp this important point. While we admit the thing in music and in letters, we fail to appreciate generally that the child’s imagination (whether in man or youth) expresses most purely the art of painting when such imagination is allowedto express itself naturally (and consequently authentically).

Gradually, however, vision pushes on into another plane and the imagination conceives the world of beauty not only on the picture plane but in space receding from the picture plane at right angles. This we may call second wind. In this stage of imaginative development the purity of painting begins to suffer because something of the lyrical poetry is sacrificed to satisfy a deepening sense of form. This deepening sense of form is satisfied by adding space to form (architecture) and shadow to light (values).

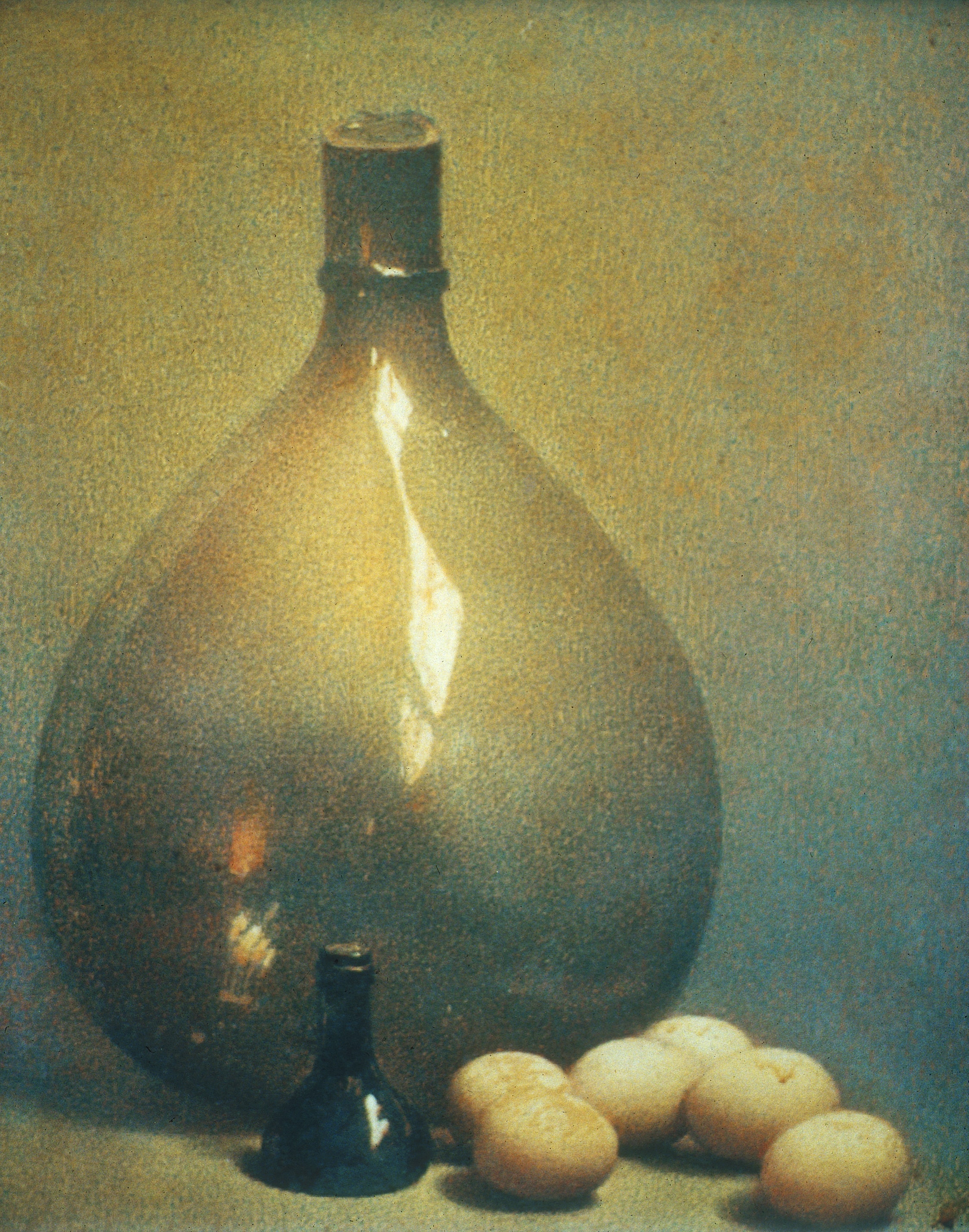

Still Life with Bottle, Oil on Canvas, Unknown date

Wind has brought, however, something greater to painting—an architectural sense to compensate for its loss of purity. As pure painting, as a lyrical art, the affair was spontaneous, entirely a matter offeeling, and it was melodic—it was “sung.” As it developed out of this stage and pursued a deeper realization of form (two-plane form united to one-plane) the imagination is raised and a picture is built as well as sung.

A problem comes into the work, which was formerly characterized by the very lack of a problem. This problem is not yet an intellectual affair. That is reserved for still more wind. But another dimension has been added to the emotional dimension. The artist’s vision now is special, and light and shade is the goal of beauty—rather than color (or light alone).

This second wind is essentially Greek in spirit and is generally formed roughly between the ages of fourteen and twenty-eight. It may be said, by the way, that where the lyrical appreciation only is seen in a person, the imagination-age of the person is 14 or under. Where the appreciation is Greek the imagination-age is twenty-eight or under. This is not meant to demean. We are lucky to find a person with any appreciation!

Wind is a hard master. The artist who has it will investigate the architectural (or two-plane) form to the fullest. Form will stand in space in its right spot on the plane. The horizontal plane will be as evident as the vertical. Design will be built as well as melodic. But void will demand a greater grasp of form. Instead of the void like the inside of a box with form arranged in relation to the space, the wind of the artist will begin to grasp form poignant, form in three-planes.

To this first vision, the lyrical vision of form suggested by light, has been added shadow and space, another plane. And to these two planes has been added a third, the diagonal, and suddenly all form is seen to be in perspective. That is, void has been conceived, and with it, complete darkness.

Void may be defined as the angular disappearance of form and space in a single point, and void is the objective of all perspective. When the vanishing point is discovered the end of three planes is conceived. To the emotional imagination has been added the special imagination and finally (with wind) the intellectual imagination, which is sculptural. For it is the nature of the creative intellect to arrive at nothing, that is, the vanishing point of three-plane form; and in so doing to give the greatest vitality and contrast to form in light. When the painter arrives at this stage of poetry, the dramatic, he has introduced the mental problem, and it is the clash of this mentality (with its very deep grasp of the converging of all things in nothing) against the emotional instinct for light and color, which gives the greatest contrast to the imagination, and consequently the greatest “kick” to beauty.

In this stage, what we may call the third-wind, a full new set of problems are thrust upon the painter. The dominant interest, of course, of sculpture and design becomes Gothic. The “singing” of a picture and the “building” of a picture have now been subordinated to the “fighting through” of a picture. That is, unity is predominantly achieved through antagonism, thrust and counter-thrust. Opposition has become the final key note of the affair, while the lyrical harmony of one-plane and the epic harmony of two-planes are, of course, not neglected. Together with the sculptural vision are combined (to complicate matters at this stage) the imaginative grasp of characterization, which must run through the whole; and most important, the rhythm of form is conceived in three dimensions.

“the student of painting or of any art must go on... he must continue with courage”

Self-Portrait, Oil on Panel, c. 1948

In a little essay of this kind one can but vaguely suggest the progress of an artist. But the point I would care to bring out and emphasize is this: that the student of painting or of any art must go on. That he start with one-plane conception of the beautiful universe but without entirely sacrificing. That he must continue with courage.

I have tried to sketch his development up to the vanishing point but may I suggest that the vanishing point is the great introduction to an art transcending Greece and even the Gothic in the beginning of the thirteenth century?

Too many painters, it seems to me, regard the study of the child as merely a preparation for the static business of painting a picture. The mastery of color and the purity of design in authentic child work are never seen in the work of the more sophisticated. Instead of growing into a successful artist who ossifies his work (finds himself) and repeats the performance for an ossified public, the wise artist is one who, with wind, pushes on. He may strain the purity of his painting to the breaking point, but if he has wind and goes on, he will contribute to beauty-offerings of great value to the few people who actually enjoy and love beauty. And the compensation in happiness outweighs the loss of a world inhabited by people engrossed in things.